Learn more about the legend...

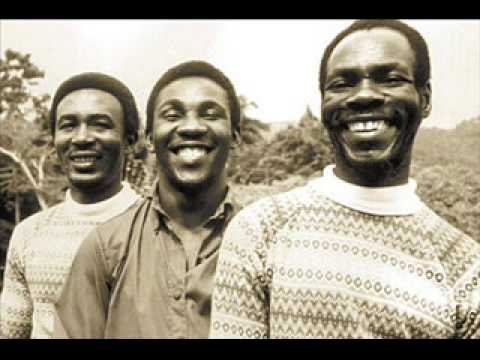

R.I.P. Reggae Legend: Toots Hibbert

December 8, 1942 – September 11, 2020

Top 3 photos by Lee Abel

The reggae world, indeed, the world-at-large, mourns the loss of reggae legend, Toots Hibbert, GRAMMY-Winning Reggae Pioneer And Founder of Toots And The Maytals. A 60-year veteran of the Jamaican music industry, Toots first used the term "reggae" in recording placing him at the foundation of a global movement.

Toots and the Maytals — one of the best known ska and rocksteady vocal groups. The Maytals were formed in the early 1960s and were key figures in popularizing reggae music. Frontman Toots Hibbert is considered a Reggae pioneer on par with Bob Marley.

By Carter Van Pelt (from 2018 Reggae Festival Guide Magazine)

The adjective “legendary” gets thrown around often describing influential musicians, but nothing could be more applicable to describe Frederick “Toots” Hibbert.

A 60-year veteran of the Jamaican music industry, the first use of the term “reggae” in a popular recording traces directly to him, placing him at the foundation of a global movement.

When “Do The Reggay” became a hit in 1968, his group the Maytals had already played an essential role in the emergence and popularity of Jamaica’s first international music: ska.

The Maytals had been around for over a decade by the time Perry Henzell’s

1972 film, The Harder They Come, brought reggae and the mystique of Jamaican counterculture to an international audience. The Maytals, whose inspirational studio performance of “Sweet and Dandy” was one of the film’s most memorable scenes, benefited greatly from their inclusion in the film and on its soundtrack. Subsequent albums for Chris Blackwell’s Island Records, Funky Kingston (1973) and Reggae Got Soul (1976), ensured that Toots and the Maytals would be standard stock in record shops worldwide and their concert appearances in demand for decades to come.

Today, the hits from Toots’ catalog are in any comprehensive review of the history of Jamaican music. More broadly, Rolling Stone named Toots Hibbert as one of the Top 100 Singers of all time.

For advanced students of Jamaican music and culture, Toots Hibbert is the greatest example of the bridge between the traditions of the

Jamaican revivalist churches and popular song, a critical nexus

in the island’s cultural mix.

Raised in May Pen, Clarendon, Hibbert was exposed from an early age to the rhythmic and melodic framework of Jamaican gospel, and of course schooled in its Old Testament narratives. While these elements are at the core of his identity, an exposure to Rastafari also marked an essential phase in the young singer’s development, as he explained to archivist Steve Barrow in a 1995 Palm Pictures interview. “I used to go to church with my parents. It was a kind of clap-hand church. They used to have concerts. I was about 12. Every time I sang, people would clap and [be] joyful. Most of my songs are coming from the church, not political really, although sometimes people may find it that way too…I was about 13, coming to Kingston, I found this church called Coptic. That’s where I was for a long, long time, just to know about the truth of Rastafari.”

It was in Trench Town, where Hibbert, then a barber, met the men who would become his singing partners – Henry “Raleigh” Gordon and Nathanial “Jerry” Matthias. “I made a four-string guitar and practice in the barber shop, sit under the guinep tree and sing. I teach them harmony and how to write songs, and they teach me how to grow up.”

After an early dubplate for King Edwards, the Maytals, then known as the Vikings, started working for a host of producers including Prince Buster, Leslie Kong, Duke Reid, Byron Lee and Coxson Dodd, the latter of whom recorded the best of their early work, anthologized on the essential LP Never Grow Old. “Ska really lift up Jamaica. It was new at the time. After boogie, you have ska…We cut a whole lot of songs [for Dodd]. We didn’t care about the money. Some of the songs maybe we want to put together better, but in those days, once you have a good voice, you just do it.”

Hibbert explains that the name Maytals comes from a colloquial phrase (essentially synonymous with “ital”) that defines his personal philosophy. “It means ‘stick together in one love.’ It means ‘natural, organic.’ Everyone who is Rasta have to be Maytal, once you say you is Rasta you have to do the right thing, maytal. It call fe a work, not just hair [dreadlocks] alone, you haffe maytal, doing the right thing. Treat people good when you can. Rasta have to be like a lamb…slow to anger – charity, love, freehearted, you always have that light shining.”

One of the Maytals’ best known songs was recorded for the island’s annual festival song competition in 1966, a government sponsored program to encourage use of traditional themes in the creation of popular music and celebration of national heritage. The Maytals won with “Bam Bam” at the same time that ska had made a transition into a slower style called rocksteady, the precursor to reggae. “Bam Bam” was built on neo-African percussive elements, consistent with the festival concept.

“When people believe in you, you have to try to do things very very very nice, in mind of what the audience might say,” he told Barrow. “This festival thing was very important. A lot of good artists entered at that time: Bob Marley, Clancy Eccles, Lord Creator, the Jamaicans, Derrick Morgan…Desmond Dekker. I came out as the number one, because my song was short and it made sense.”

As Hibbert told Barrow, the word “reggae” developed as another colloquialism in Kingston in the late ‘60s. Reflecting the fluid nature of new words, it was applied to an emerging musical style and its accompanying dance, distinguishing these from rocksteady. The Maytals took the street lingo, a derogatory slang term, and made it into a song. “One day [in Trench Town] myself, Raleigh and Jerry was sitting down, rehearsing, and there was a guy next door talking to a girl, a nice girl, but just for argument sake, we always say ‘streggay.’ Just a little vibe. If someone is going on and you don’t feel to talk to [her], you just say [s]he’s streggay. So we just say, come on, let’s do the reggay.” Among other highly recognizable hits in the Maytals catalog is, of course, “54-46 (Was My Number),” Hibbert’s narrative of his prison experience resulting from a ganja frameup.

While the song’s reference to marijuana is oblique, it has become a resistance anthem with dozens of covers and derivative versions. “They told a lie on me, and I went to prison, [but] they hurt [from it] more than me, because I wrote about it.” Due in part to its inclusion on The Harder They Come soundtrack, “Pressure Drop” has also become one of Toots’ most enduring songs, ever present in his live sets. As he explains, the “pressure drop” implied in the song is not literally in reference to barometric pressure, but rather to oppression.

“Pressure have to drop in order to make the people survive. The people need the pressure to drop, through all the world.” Hibbert is always quick to acknowledge the remarkable run he’s had with members of his backing band, who were with him since recording for Beverley’s (Leslie Kong) and on many subsequent recordings, as well as decades of touring. Guitarist Hux Brown, bassist Jackie Jackson, drummer Paul Douglas and organist Winston Wright gave the tracks recorded at Dynamic Sounds a professional musical arrangement and studio clarity that reggae needed in its early years, as it was often derided as being simplistic. Douglas and Jackson have been a consistent part of Hibbert’s live shows for over 40 years. Hibbert’s self-productions date back to the late 1970s, and he has released a steady stream of quality material ever since. In 2004, the Richard Feldman production, True Love, helped revive Toots’ career once again and placed him with other stars of global stature, including Willie Nelson, who counts himself among the singer’s many accomplished admirers.

In 2018, along with fellow reggae icons Jimmy Cliff and Ken Boothe, Hibbert is the last of the high-profile stars of his generation still performing. A well-documented concert hiatus from 2013 to 2016, due to a stage injury, deprived his fans of his inspired and energetic live shows. He has returned to live performance gradually since 2016 and is on the road at age 76 with dates on the East and West Coasts of the U.S.

During his interview with Barrow, Hibbert makes clear his faith and his understanding of his own work as the fulfillment of a greater design. “Everyone who listen to my music, they say it revive their spirit. If they was down, the music just lift them up. I [am] really proud of that. It wasn’t me by myself, it was the power of the Most High, as I say.” The writer wishes to dedicate this piece to the memory of Toots’ manager, Mike Cacia, who passed away in 2017.

Carter Van Pelt has been a radio producer and host since 1991 and is founder of Coney Island Reggae On The Boardwalk.